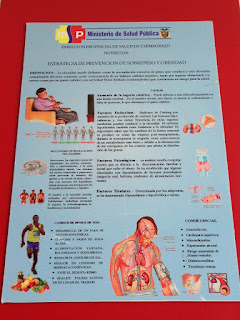

There exists an inextricable link between the public health department and the community clinics in Riobamba. The clinic is divided into departments based on the biggest community health needs: vaccines, maternal health, chronic diseases, nutrition, etc. There is an entire room which simply houses statisticians. The wall just to the left of entering the room is covered with various graphs, pie charts, and tables depicting current health trends and the incidence/prevalence of various conditions. This information is collected directly at the clinic and helps to inform how services and resources will be distributed. Throughout the clinic, public health signs caution against the symptoms of tuberculosis, provide tips on preventing obesity, and note the warning signs of preeclampsia/eclampsia.

Maternal mortality is one of the most serious health problems throughout the country and the large number of teen pregnancies contributes largely to the high numbers. In many ways, Ecuador has made significant strides in addressing the health needs of its people, but in this area the struggle continues. The public health campaign is battling against a tide of currently accepted cultural behaviors.

Community clinics blatantly advertise various contraceptive options - OCP's, Implanon (nexaplon isn't being used yet), IUD's, etc. Undoubtedly, in parts of the country where access to medical services is harder to come by, decreased use of contraception is understandable. But in areas where services are readily available, what are the barriers to use? I suspect that some of the reasons are the same as in the states - lack of pre-planning, inconsistent use, fear of side effects, costs, privacy concerns. But in Ecuador, the cultural norm of teen pregnancy plays a large role. Simply put, teen pregnancy isn't considered unusual. While on one hand, this ensures that many teens have the support of their families during pregnancy and in caring for their children; on the other hand, this relative normalcy makes it difficult to counsel young women regarding the severely increased risk of maternal complications and prevent these higher risk pregnancies. And beyond the direct health impact, there exists the socioeconomic impact of limiting women's ability to further their education, employment, and social advancement.

The following three 17 year old patients, illustrate some of the current challenges facing young women in Ecuador.

Mavia* is 17 years old and works in the clinic as part of the janitorial staff. She recently retook the equivalent of the SAT's and is awaiting her results next week to determine if she can apply to university to study nursing or to become a lab technician. To qualify for the program she needs at least 850 points on the exam. The last time she took it, she got 816 points. She's concerned because each semester will cost $500 (the Ecuadorian currency is the U.S. Dollar) and doesn't know if she'll be able to study and work at the same time. However, she's optimistic about the future and isn't willing to give up on her dream easily.

Daniela is 17 years old and belongs to an indigenous group of Ecuadorians. She speaks both Quichua and Spanish. She's been married for less than a year. Her husband travels for work and has been gone for about two months and is returning this week. She wants to discuss contraception options as she doesn't want children yet. After a lengthy discussion she decides on Implanon and receives a prescription so she can purchase the Implanon and return to the clinic to have it placed.

Maricela is 17 years old and 38 weeks and 3 days pregnant. She started noting lower abdominal pains yesterday and presents today with her father because she thinks something is wrong. Her partner is currently at work. After a few minutes, it's apparent that Maricela is in the early stages of labor. She receives extensive counseling on the symptoms of labor, what to expect, and went to present to the hospital.

*names have been changed

No comments:

Post a Comment